Combining remote sensing technologies makes wind turbine impacts easier to study

Combining multiple sensors when surveying wildlife can improve data quality.

Background

Estimating collision and displacement impacts on birds and bats from wind turbines is expensive and laborious, given the extensive human labor needed to count carcasses underneath turbines or conduct behavioral avoidance surveys. To reduce costs and labor associated with collecting bird and bat mortality data, remote sensing equipment enables continuous data collection without relying on laborious field surveys. Remote sensing equipment commonly used to study collisions and displacement impacts from wind turbines includes cameras, acoustic sensors, radar, radio tags, and blade-impact sensors. A new study by Dempsey and colleagues examined the benefits and drawbacks of different sensor types and how combining sensors (fusion) can partially address the limitations of any one sensor.

How the study was done

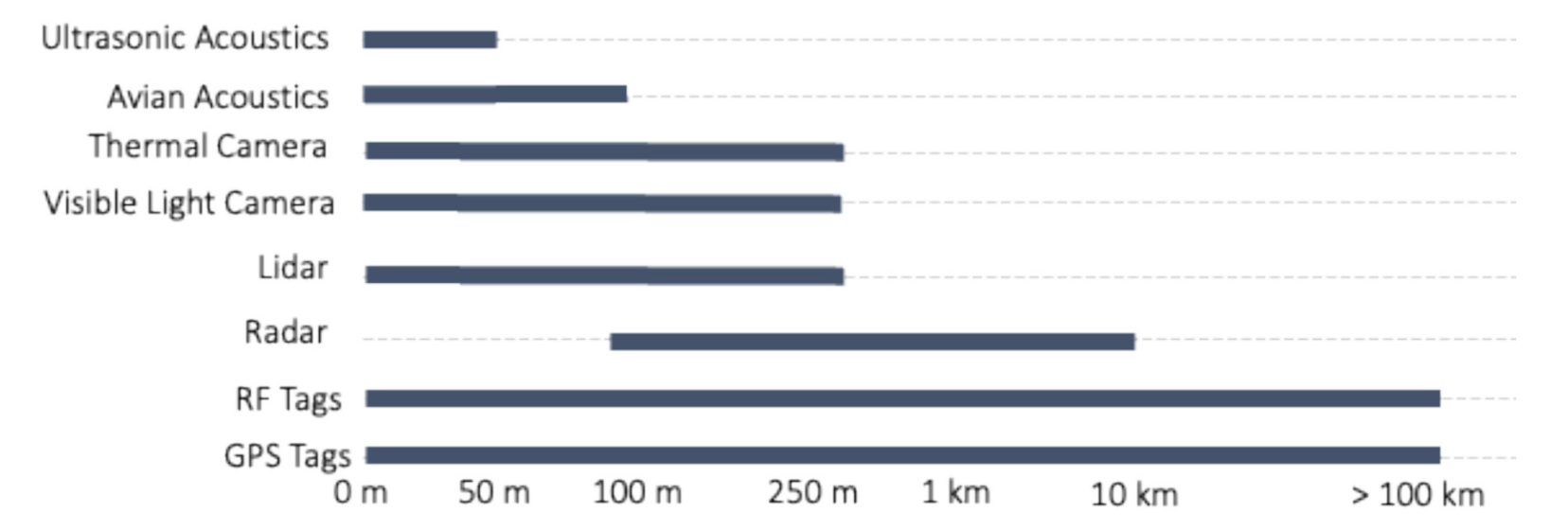

Dempsey and colleagues conducted a desktop review of multiple sensor technologies commonly used to assess collision and displacement effects from wind turbines. The authors reviewed numerous sensor types, including cameras, acoustic sensors, radar, lidar, and radio-frequency tags. Each sensor collects different types of data (i.e., imagery, acoustic recordings, tag detections, etc.) and works optimally at different scales (Figure 1). Choosing a sensor type depends on the species of interest, the study goals, and whether collisions or displacement is the focus of the study.

Technology for Monitoring Collisions

Collision mortality at wind facilities occurs when birds or bats impact spinning blades and die from blunt trauma. Counting collisions at terrestrial wind facilities is typically done by ground-based observers or dogs searching predetermined areas for carcasses. The observed number of carcasses is converted into a project-wide mortality estimate using a statistical estimator that accounts for the area sampled, observer bias, and the time carcasses remain in the environment before decomposing or being removed by scavengers. Observed carcass counts serve as a proxy for total project mortality, as human observers are unlikely to directly observe collisions because they are rare. Therefore, monitoring an entire wind facility using human observers would require too many observers to be feasible.

Limitations of human and dog observers can be largely addressed by current remote sensing technologies. Thermal and visible-light cameras can monitor wind turbine rotor swept zones for collisions without being subject to observer bias or fatigue. Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR) can provide 3D tracking data on targets flying in the rotor swept zone and around the turbines. Collecting behavioral data, particularly related to turbine attraction, is more feasible with cameras than with human observers because flight activity can be observed around the clock, in all weather conditions, without requiring observers to be stationed offshore. A better understanding of attraction is critical for understanding the mechanisms influencing collision risk and developing effective strategies to reduce collisions.

While camera systems are a promising technology for monitoring mortality at wind facilities, they have a limited field of view and have limited ability to identify species, depending on visibility and image quality. Field of view can be improved by integrating multiple cameras into a system, and species identification can be improved by combining visible-light cameras with thermal cameras and acoustic sensors. Other sensors that monitor blade vibration can indicate the exact times and locations of collisions, thereby aiding the localization of targets in the video for behavioral analysis and species identification.

Displacement

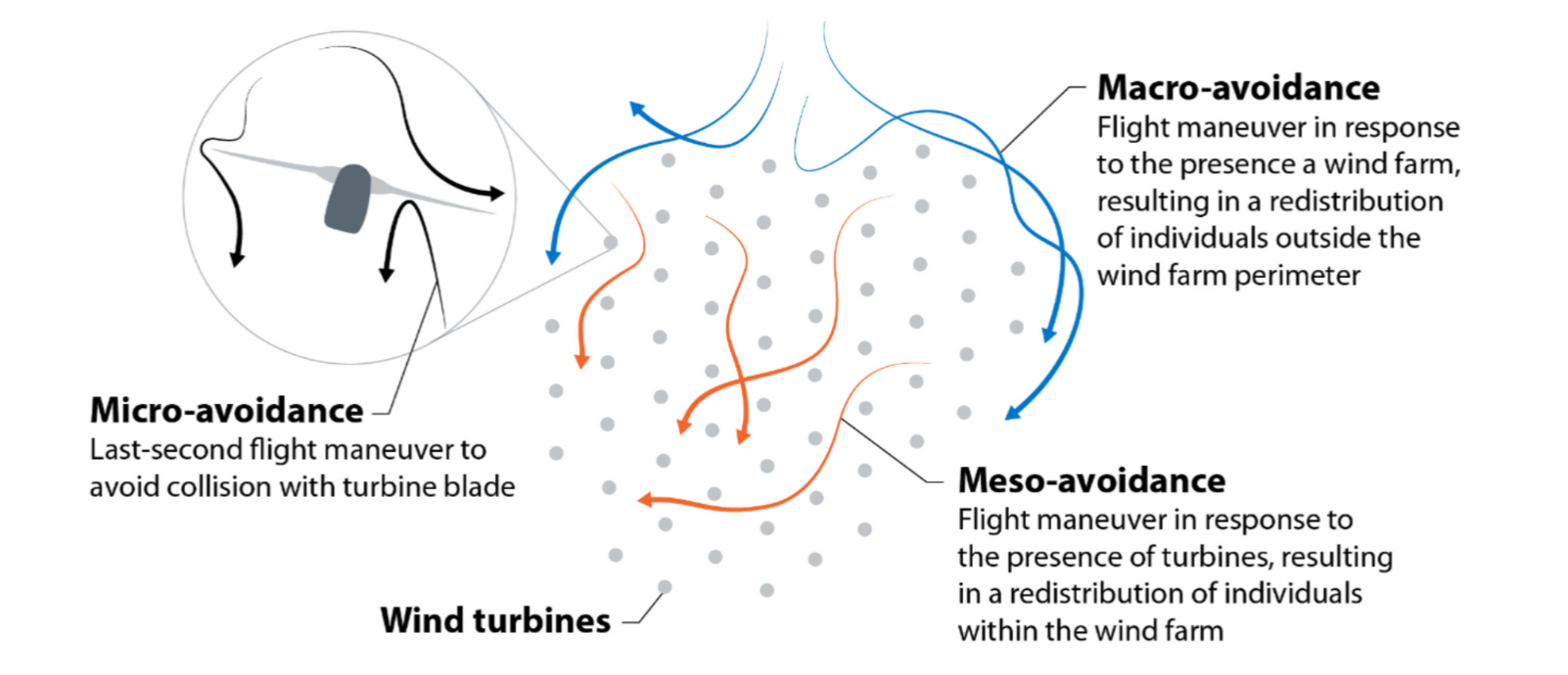

Displacement occurs when animals avoid unsuitable habitats or areas with barriers, such as wind turbines. This behavior can render large areas of ocean habitat less desirable (macro avoidance) or can help birds and bats avoid collisions with turbine blades (micro avoidance) (Figure 2).

Displacement is difficult to study because the effects are less noticeable and don’t cause direct mortality; therefore, displacement must be studied by first separating the effects of natural changes in wildlife distributions from human-caused changes. Thus, studying displacement requires long-term monitoring to understand changes in species presence, activity, and movement patterns. Remote sensing is particularly well-suited to long-term offshore monitoring, given the high costs and challenging logistics of deploying human observers in inaccessible environments. Acoustics and cameras are useful for studying micro-avoidance, whereas radar and tagging sensors are more suitable for studying macro- and meso-avoidance.

Acoustic sensors provide a reliable and cost-effective means of continuously monitoring birds and bats that frequently vocalize, such as migrating bats and migratory songbirds. However, acoustics are not useful for species that infrequently vocalize, and it is impossible to count the number of individuals based on the number of acoustic recordings, especially when individuals move in and out of the detector range. Although acoustic detection range is limited, these sensors can be combined with other longer-range sensors to improve data collection.

Determining displacement at larger scales is best done with radar, as these sensors can sample more airspace at longer ranges than other sensors, at the cost of less species-specific and behavioral information on interactions with turbine blades. Radar can quantify large-scale displacement by comparing flight-track densities within the project area with those outside it. However, these comparisons may require multiple radar units, depending on project size, thereby substantially increasing monitoring costs.

Displacement effects can also be quantified at large scales by tagging and tracking individual birds, either with radio-frequency or GPS tags. GPS tags provide higher-resolution data but are more expensive and too heavy to attach to small birds and bats. Tracking movements with radio-frequency tags also requires a network of receivers to be installed in the area of interest to detect the tags. The necessity of a network of radio receivers limits the spatial resolution of movement data, but it does offer a lower-cost approach to tracking broad-scale wildlife movements. Understanding displacement from tagging studies involves comparing movement data from pre-construction studies to similar data collected post-construction. Combining tagging studies with other sensors can provide tracks of known species to radar sensors, thereby improving track classification and enabling large-scale movement data with species-level identifications.

Understanding vulnerability with models

Collecting data from multi-sensor systems can provide insights into bird and bat vulnerability from offshore wind, but drawing conclusions from those data require more in-depth analysis. Models provide a way to take input data and, through an algorithm, understand how different values can affect predicted vulnerability, collision risk, and displacement risk. Using 3D flight tracks, species identification, and avoidance data, collision risk models, and selective assumptions, researchers can make predictions about collision risk and understand the factors that influence that risk.

Collision risk to bats is often related to wind speed; as wind speed increases, bat activity and associated risk commonly decrease. However, other drivers of bat collision risk remain poorly understood. Remote sensing technologies can help elucidate other environmental factors that drive attraction to turbines and, consequently, better explain why bats collide with them. Cameras and collision sensors can also record the exact timing of collisions, providing more precise data for determining causal factors that influence collisions.

Conclusions and Recommendations

The study by Dempsey and colleagues concludes with recommendations to adopt an iterative framework for developing offshore monitoring approaches. Wind-wildlife monitoring systems should be able to not only monitor for effects to test the effectiveness of any mitigation, but also monitor the drivers of collisions and displacement. However, the exact specifications of any monitoring system depend on the species of interest and the study’s goals. Combining multiple sensors into a single system is the most effective way to overcome the limitations of any single sensor. Despite the benefits of remote sensing equipment for collecting offshore data, there are notable disadvantages Including hardware downtime, data storage, and equipment costs. However, given the logistical constraints of offshore access for human observers, remote sensing is the only realistic means of collecting long-term baseline data on wildlife. These data will be critical for future understanding of the large-scale impacts of offshore wind.

References

Dempsey, L., J. Clerc, and C. Hein. 2025. New frontiers in wind-wildlife monitoring systems. Biological Conservation 311:111449. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0006320725004860